Introduction

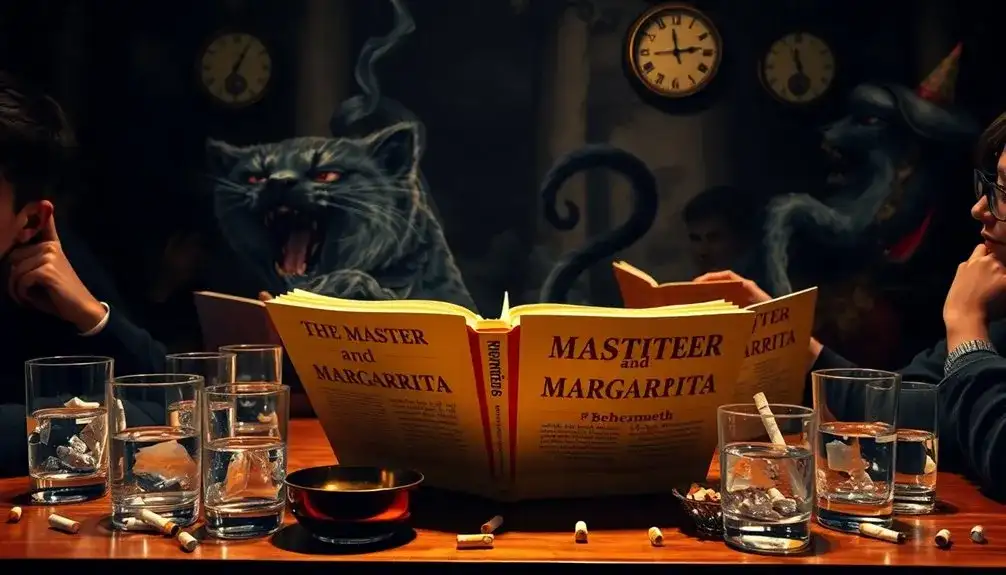

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita remains one of the most enigmatic and powerful novels of the twentieth century. Set against the backdrop of Stalinist-era Moscow, the novel weaves together satire, magical realism, biblical allegory, and philosophical inquiry into a seamless and often surreal narrative. With its richly layered characters, dual timelines, and timeless themes of good versus evil, love, and artistic freedom, this work has captivated readers for decades. Its continued relevance is evidenced by a high reader rating and ongoing critical discussion across literary circles worldwide.

This article provides a comprehensive, organized analysis of The Master and Margarita, exploring its major themes, characters, symbolism, literary style, critical reception, and enduring legacy. Readers will gain a deeper appreciation for the novel’s complexity and Bulgakov’s literary genius.

Overview of the Novel

At its core, The Master and Margarita intertwines two primary narratives. One is set in 1930s Moscow, where the devil, under the alias Woland, visits the Soviet capital and creates havoc among its citizens. The other takes place in ancient Jerusalem and follows Pontius Pilate as he grapples with his conscience during the trial of Yeshua Ha-Notsri (Jesus Christ).

These storylines are connected by themes of power, morality, and artistic integrity. The Master, a reclusive author in Soviet Moscow, has written a manuscript about Pilate and Yeshua but has been persecuted for it. Margarita, his devoted lover, embarks on a magical and transformative journey to rescue him, ultimately restoring his spirit and their shared love.

Through fantastical elements, biting satire, and deeply philosophical questions, Bulgakov critiques Soviet society and explores universal concerns that transcend time and place.

Central Themes

Good Versus Evil

One of the novel’s most prominent themes is the complex interplay between good and evil. Woland, though the devil, often acts as a force of truth, exposing the hypocrisy, greed, and corruption of Soviet officials and intellectuals. His presence forces characters to confront their moral failings, suggesting that evil, paradoxically, can reveal deeper truths.

Pontius Pilate’s narrative furthers this exploration. Faced with the opportunity to save an innocent man, Pilate succumbs to political pressure, embodying moral weakness. His internal torment symbolizes the universal struggle between conscience and duty.

Artistic Integrity and Censorship

Bulgakov’s life under Soviet censorship deeply informs the novel’s portrayal of artistic struggle. The Master, an alter ego for Bulgakov, is a writer driven to madness after his manuscript is rejected by the state-run literary establishment. Margarita’s defiant pact with the devil to save him reflects the sacrifices artists make to preserve their vision and truth.

The phrase “manuscripts don’t burn,” spoken by Woland, becomes a powerful metaphor for the indestructibility of art and ideas, even under totalitarian repression.

Love and Sacrifice

The novel’s emotional center lies in the relationship between the Master and Margarita. Their love defies logic, convention, and even death. Margarita’s willingness to endure humiliation and make a deal with supernatural forces for the Master’s sake highlights love as a redemptive, transformative force.

Their union ultimately transcends earthly boundaries, offering a vision of peace and fulfillment in an afterlife shaped not by punishment, but by compassion.

Satire and the Absurdity of Soviet Life

Bulgakov’s satirical lens reveals the absurdities of daily life under the Soviet regime. Woland’s magical escapades in Moscow—ranging from turning currency into worthless slips of paper to making bureaucrats vanish—highlight the moral decay and irrationality of a society obsessed with control and conformity.

Characters like Berlioz, the literary bureaucrat, and the bumbling poet Ivan Bezdomny, illustrate the suppression of creativity and truth in Soviet Russia.

Author’s Background

Early Life and Medical Career

Born in Kyiv in 1891, Mikhail Bulgakov initially pursued a career in medicine. His training exposed him to human suffering, which later influenced his empathetic portrayal of characters caught in moral and existential crises. His experiences during the Russian Civil War further shaped his disillusionment with authoritarian ideologies.

Transition to Writing

Bulgakov left medicine to become a full-time writer, contributing to newspapers and theaters. His early plays and novels gained modest success, but he faced increasing censorship. By the 1930s, his works were routinely banned or heavily edited, pushing him into semi-obscurity.

Struggles with Censorship

Censorship became a defining force in Bulgakov’s life. His work often conflicted with official Soviet ideology, leading to isolation and despair. Despite this, he refused to abandon his literary ideals. He began The Master and Margarita in the 1930s, rewriting it multiple times and hiding it from authorities. The novel wasn’t published until over two decades after his death.

Posthumous Recognition

The Master and Margarita was first published in 1966 in a censored version. Its bold critique of Soviet society and its imaginative scope quickly captured readers’ imaginations. The unabridged version, released later, cemented Bulgakov’s status as a literary icon.

His phrase “manuscripts don’t burn” became a rallying cry for artistic freedom, ensuring his work’s lasting legacy.

Main Characters

Woland

A devil figure in the novel, Woland challenges traditional perceptions of evil. Far from being a one-dimensional villain, he enacts a kind of cosmic justice, punishing the corrupt and rewarding those who show courage and love. His supernatural retinue, including the talking cat Behemoth, adds layers of humor and absurdity.

Margarita

Margarita is perhaps the novel’s most compelling character. Her love for the Master drives her transformation into a witch, granting her both freedom and power. Her strength, compassion, and courage stand in stark contrast to the weakness of many male characters. She represents the indomitable human spirit.

The Master

A tormented author, the Master is a stand-in for Bulgakov himself. Broken by the rejection of his manuscript, he retreats into anonymity. His love for Margarita and his writing eventually restore his sense of self. His journey illustrates the emotional toll of censorship and the redemptive power of personal truth.

Pontius Pilate

In the parallel narrative, Pilate struggles with the decision to execute Yeshua. His internal conflict embodies the broader moral ambiguity of power and obedience. Pilate’s guilt lingers eternally, suggesting that moral failure carries long-lasting consequences.

Yeshua Ha-Notsri

Representing a Christ-like figure, Yeshua promotes compassion, peace, and understanding. His philosophical dialogue with Pilate elevates the narrative beyond religious allegory, inviting readers to reflect on justice and humanism.

Literary Style and Techniques

Magical Realism and Surrealism

Bulgakov seamlessly blends the fantastical with the mundane. Supernatural occurrences unfold in everyday Soviet life, creating a dreamlike atmosphere that mirrors the absurdity of totalitarian existence.

Symbolism and Allegory

Symbols such as yellow flowers (representing love and passion), the moon (mystery and transformation), and manuscripts (artistic permanence) enrich the narrative. Woland’s retinue reflects various facets of society, from bureaucracy to intellectual elitism.

Dual Narrative Structure

The alternating storylines of Moscow and Jerusalem allow for a rich juxtaposition of modern repression and ancient moral dilemmas. This structure emphasizes the timelessness of the novel’s central questions.

Dialogue and Irony

Sharp, witty dialogue underscores the novel’s satirical edge. Bulgakov uses irony to highlight societal contradictions and moral compromises, often to humorous effect.

Reception and Critical Acclaim

Upon its release, The Master and Margarita was hailed as a literary revelation. Critics lauded its originality, depth, and bold critique of Soviet society. Its rating of 4.29 based on hundreds of thousands of reviews reflects its enduring appeal.

Today, the novel is studied in universities, adapted for stage and screen, and embraced by readers around the world. Scholars admire its layered complexity and rich intertextuality, drawing comparisons to Goethe’s Faust, Kafka’s The Trial, and García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

Artistic Influence

The novel’s influence extends beyond literature. Musicians like the Rolling Stones have referenced it in their lyrics. Theatrical adaptations bring its fantastical elements to life, while artists and illustrators continue to explore its vivid imagery.

Social Commentary

The phrase “manuscripts don’t burn” has become symbolic of intellectual resistance. The novel continues to inspire movements for artistic freedom and human rights.

Global Relevance

Though deeply rooted in Soviet history, The Master and Margarita speaks to universal issues: state oppression, personal freedom, love, sacrifice, and the pursuit of truth. It remains relevant in an age still grappling with censorship, disinformation, and moral ambiguity.

Reader Experiences

Emotional Responses

Readers often report strong emotional reactions to the novel. Margarita’s loyalty, Pilate’s guilt, and the Master’s despair resonate across cultures. The novel’s balance of humor and tragedy provides catharsis and reflection.

Community Engagement

Book clubs, online forums, and academic symposia frequently discuss the novel’s themes, characters, and symbolism. Many readers return to the novel multiple times, finding new insights with each reading.

Timeless Appeal

From nostalgic quotes to seasonal rereads, The Master and Margarita remains a personal favorite for many. Its emotional and intellectual depth ensures that it never grows old.

Comparisons to Other Works

Goethe’s Faust

Woland mirrors Mephistopheles, tempting humans and revealing deeper truths. Like Faust, the Master seeks knowledge and love at great personal cost.

Kafka’s The Trial

The absurdity and helplessness of Soviet bureaucracy echo Kafka’s nightmarish visions of authoritarian control.

García Márquez and Magical Realism

The novel’s dual timelines and seamless blend of magic and reality prefigure the Latin American tradition of magical realism.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies

The tragic love story of the Master and Margarita evokes comparisons to Romeo and Juliet, underscoring the theme of love’s endurance amidst chaos.

Conclusion

The Master and Margarita is more than a novel; it is a profound artistic statement that challenges, delights, and moves its readers. Mikhail Bulgakov’s fearless blend of satire, romance, philosophy, and fantasy invites us to reconsider the boundaries between reality and imagination, good and evil, love and loss. In a world still wrestling with repression and uncertainty, the novel’s message rings clear: truth endures, love redeems, and manuscripts don’t burn.

This literary gem continues to captivate hearts and minds, affirming Bulgakov’s place among the greats of world literature.